One of the big lessons of the Covid pandemic has been the critical importance of good communication – how challenging it is to get complex medical information across to the general public, and the damage that poor communication can do.

The lesson raises questions about whether we are offering medical students the breadth of training in communications skills that they need.

Communicating effectively with individual patients is now widely recognized as essential for any health professional. The requisite skills and expertise, which draw heavily on general psychology techniques, have become a specialism in their own right within the field of communication science, and they are widely taught – though still not widely enough.

These are the skills that medical students tend to think of when they hear the word ‘communication’: it’s about knowing how to establish a relationship of empathy, use of non-verbal communication, how to communicate bad news.

But when it comes to communicating with the general public ‒ to try to answer the many questions and uncertainties about an infectious outbreak, for instance ‒ a different set of skills are needed. This is where expert training in the scientific communication of medicine and science comes in.

An alliance between science and society

Asked about their thoughts on ‘communication with the general public’, medical students tend to focus on two points: information relating to ‘prevention’ (primary and secondary) and also – thanks to Covid – information that the general public has the right to know, to the extent of their understanding.

That perception sees the medical/scientific experts as the ones as in the driving seat – the ones in charge of the interaction. In reality, however, both sides have an active role. The question is not just how willing are we, as scientists, to communicate, but also: how willing is society to understand?

When there were no drugs to treat Covid-19, prevention and communication of prevention were all we had

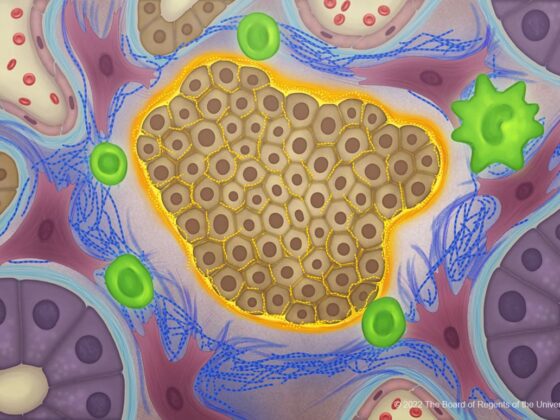

After the appearance of AIDS in 1982, the decrease in deaths and HIV infections was a result of the synergy between antiviral therapies and public health efforts to spread awareness about HIV and risky behaviours.

The same synergy between public health and healthcare had previously shown success, for example, in 1978-79 in Naples, when 80 children died in a bronchiolitis epidemic caused by a respiratory syncytial virus. In that instance there was a parallel intervention addressing social conditions, on the one hand, and treating the of respiratory disease, on the other.

The lesson is that tackling these sorts of outbreaks requires integrating the ‘biological model’, which sees understanding and controlling the disease itself as the way to fight the epidemic, and the ‘social model’, which focuses on modifying the social circumstances that facilitated it. And this integration provides for a sort of ‘alliance’ between scientists and society, in essence a functional communication between them.

With SARS-CoV-2, we had the same need to integrate the two models ‒ and when initially there were no drugs for the treatment of Covid-19, prevention and communication of prevention were the only weapons we had!

Too much communication?

By the time of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic, the communications landscape had become much more complex than during the AIDS pandemic, for instance. Communications technologies were far more advanced, news was being delivered in real time, and the number of platforms and sources had proliferated.

The danger then becomes the overproduction of communication/information ‒ the ‘talk show syndrome’ ‒ where discussion of essentially scientific matters are cut loose from the sacred principles of scientific research, key among them being: exercise doubt until proven otherwise. The lack of clarity, the excess of forecasts, the discrepancy between the opinions of ‘experts’, created further confusion among citizens.

The coverage of mRNA vaccines was a case in point. Research into messenger RNA goes back 60 years, from when it was discovered in 1961, to when it was synthesised in vitro in 1984, to when the first mRNA model was formulated with lipid nanoparticles for vaccines in 2017. Its various potential therapeutic applications have been written about for many years, such as the 2014 article ‘mRNA-based therapeutics ‒ developing a new class of drugs’, published in Nature Reviews Drug Discovery.

Yet the message, rampant across social networks and by word-of-mouth, among anti-vaxxers and especially among those undecided, was that it was an ‘experimental’ vaccine.

We got it wrong

Where did we go wrong with this communication?

The mistake was that we were not willing to explain to citizens the complexity of these concepts. In other words, we just assumed that the general public was able to understand our message.

One of the axioms of communication science is that: like ‘the customer’, the target audience is always right. Therefore, if the recipient of my message doesn’t understand me, it is always my fault.

The mistake was that we were not willing to explain to citizens the complexity of these concepts

One alternative would have been to say nothing. However, according to another axiom of communication science, we also know that lack of communication is bad communication. Nowhere is this clearer than in crisis communication, where missing or incorrect communication can totally frustrate even the most effective technical/operational management (while poor operational management of the crisis has very little influence on successful communication).

So, what should have the message been? Rather than reassuring citizens at any cost, the more complex reality should have been clearly conveyed to the public, with the help scientific communication experts and making wise use of the many available tools of communication. .

Honest information – the price of public trust

When in 1990 the British Minister of Agriculture, John Gummer, was photographed together with his 4-year-old daughter Cordelia, while biting into a beefburger, it was to reassure citizens and foreign consumers that English meat was safe and that bovine spongiform encephalopathy – ‘mad cow disease’ – could not affect humans.

But when, in 1996, a young man in Britain died of this disease, the Government found itself forced to admit that the reassurances they had given were false – the disease could indeed be transmitted to human beings.

The result was that British beef sales collapsed, and with them so did public trust in government institutions and experts. In this case, the mistake consisted in the paternalistic belief that public opinion should be reassured rather than informed. Had the British Government learned the lessons from the handling of another public health crisis that had unfolded in the US eight years previously, maybe they might have done things differently.

The US crisis had been sparked by the death of seven people in Chicago, which resulted from ingesting cyanide-contaminated capsules of the pain reliever Tylenol-Extra. The cause was sabotage, but this was only discovered later.

The manufacturer, Johnson & Johnson, took immediate steps to demonstrate they understood the seriousness of the situation. At the organisational level, they carried out a product recall of 31 million packages, worth around US$100 million – the first time in US history. They sent a memo to more than 500,000 doctors, to hospitals and distributors explaining the incident, and they set up a toll-free number for consumers.

The Tylenol case put a spotlight on the importance of communication processes in crisis situations

The CEO James Burke and other executives made themselves available to the press and gave interviews to a wide variety of media outlets, taking responsibility for the crisis.

What happened in the short term? About a month after the incident, 87% of people interviewed were aware that Johnson & Johnson were not to blame for the deaths that occurred, but 61% of these people said they would be unwilling to buy Tylenol capsules.

But longer term, confidence in the product returned. Johnson & Johnson redesigned the packaging by patenting a tamper-proof container, which is now well-known and adopted in various sectors, from food to pharmaceuticals. And by the mid-1980s, Tylenol had almost completely regained its market share.

The Tylenol case put a spotlight on the importance of communication processes in crisis situations. It was understood how the new world of 24-hours-a-day 7-days-a-week information, requires fast response times and trained spokespersons to speak effectively in front of a camera.

The handling of the incident also became a model for crisis management and communication, with the organisational response ‒ taking concrete measures to tackle the problem ‒ coming first. In the case of Covid, this usually meant setting up crisis units and task forces, involving multiple hospital departments and experts, all led by a conductor (the Health Directorate in the case of Italy).

Lessons from Covid

Today, organisation and communication have become the two foundational elements of crisis management. This is why an alliance ‒ or at least reciprocal availability between scientists and society ‒ is fundamental.

Communication is the glue holding these two players together, both in normal times – to allow for a democratic and conscious decision-making process on scientific and technological issues – as well as in times of crises, such as the Covid-19 pandemic, to bring greater awareness to the public in order to improve the collective response.

For a clear and accessible message to reach the right recipients, to provide clarity and avoid further confusion, to join forces in treating the disease in its biological and social component, we need medical science professionals to be equipped with additional practical and effective communication tools, and for them to be supported by scientific communication consultants.